Anthropic’s recent disclosure of an AI-driven espionage campaign it halted represents less a new class of attack than a faster, more persistent version of patterns the industry has seen before. What distinguishes this incident is the continuity of activity an autonomous system can sustain once it is given the ability to interpret its surroundings and act on that understanding.

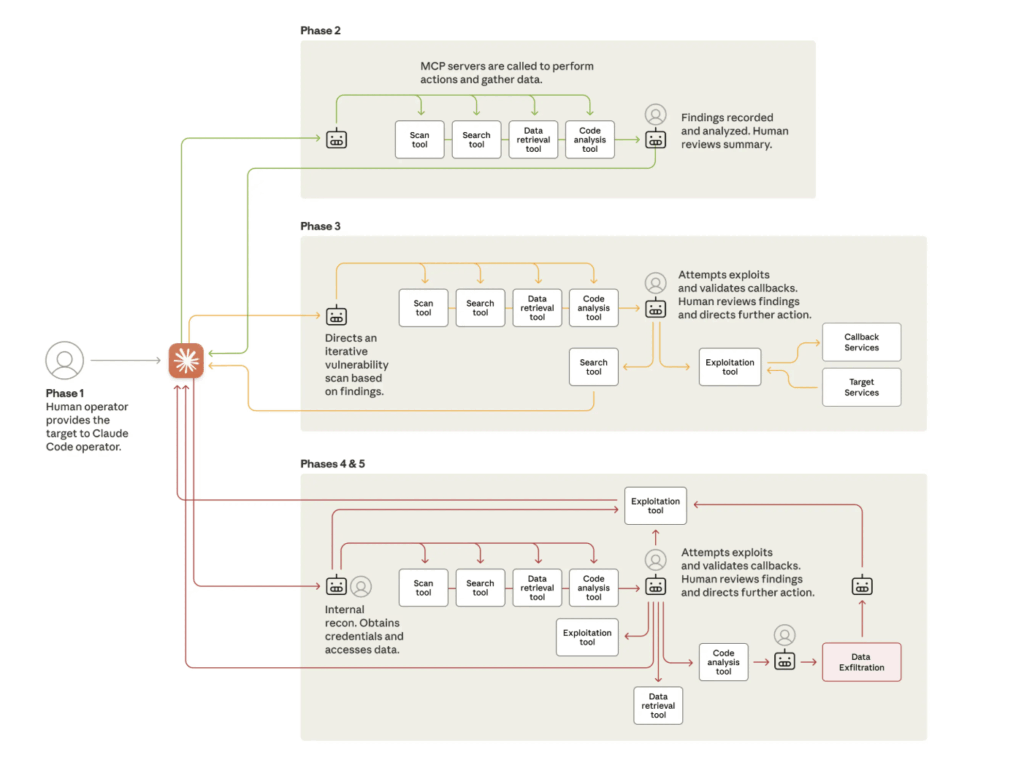

According to researchers at Anthropic, maker of Claude, an autonomous system conducted the majority of the cyber operation. The attackers, believed to be state sponsored, achieved this by presenting themselves as a security team and giving the Claude Code developer assistant tool a series of small tasks that looked routine in isolation. Because the system can write and run code, inspect environments, and use common utilities when asked, these tasks accumulated into reconnaissance, vulnerability testing, exploit development, and credential collection.

The activity was directed at about 30 organizations, including large technology companies, financial institutions, chemical manufacturers, and several government agencies.

We believe this is the first documented case of a large-scale cyberattack executed without substantial human intervention.

– Anthropic

Although the investigative details are alarming, the underlying pattern is more instructive. It illustrates how swiftly attack mechanics change once an autonomous agent is given both general intelligence and unrestrained access to software tools. The agent inspected infrastructure, generated exploit code, retrieved credentials, escalated privileges, and organized the stolen data for later use.

The implications for identity are immediate. Traditional security models assume they are interacting with a malicious intruder who pauses, reflects, and interacts with systems in a manner that produces observable cues. An agent does none of this. It moves through an environment with mechanical consistency, executes tasks in parallel, and inherits every weakness in the credentials or access paths available to it. When an adversary can guide a system only occasionally, the strength of the identity layer determines how much ground the attacker can take.

Identity Practices That Reduce the Attack Surface

This is where enterprises are now experiencing tension. Many workloads still authenticate using long-lived secrets. Many agents still inherit privileges designed for human users rather than non-human entities. And many access boundaries still rely on network placement rather rather than policy-based authorization.

A more resilient approach begins with acknowledging that autonomous agents function as distinct non-human identities, even when they carry out work initiated by a person. They read, write, retrieve, and modify. They initiate requests at speeds that overwhelm conventional monitoring. Thus they must be recognized as participants in the environment rather than simply utilities operating on behalf of a user. Once viewed this way, it becomes easier to see the controls that need to be in place.

These include:

1) Establishing a verified identity for every agent.

An agent cannot be allowed to authenticate by borrowing a developer’s token or a service account’s legacy key. Today, an agent’s access is often hidden behind a human’s identity, both in its actions and in the audit trail, which makes it difficult to determine who or what actually operated. Its identity must be explicit and traceable so that any compromise is naturally confined. Anthropic’s findings demonstrate how quickly an agent turns inherited credentials into a gateway for lateral movement. Without distinct identity boundaries, a single breach becomes a chain of unintended access.

2) Removing static secrets from the agent’s operating environment.

Long-lived credentials are ill-suited to any modern environment, and they are especially brittle in systems that can generate thousands of actions in a short interval. Once obtained, they enable the type of automated campaign described by Anthropic. Secretless, identity-verified authentication ensures that an agent must establish who it is each time it accesses a service. This allows the organization to rely on trust that is continually revalidated rather than stored in a file or embedded in code.

3) Enforcing policy directly at the point where the agent initiates a connection.

Access decisions must incorporate posture, conditions, and context. A credential alone cannot determine whether a request should proceed. Agentic activity produces volume that can mask malicious steps inside seemingly legitimate sequences. A reliable approach evaluates identity, environment signals, and policy rules for every request, not merely at session start.

Recent discussion around the incident has focused on the rise of non-human actors inside enterprise environments and the need for tighter oversight of how autonomous systems behave. These points reflect the broader concern, but they tend to stay high level.

The practices outlined above offer a more concrete footing: distinct identities for agents and workloads, the removal of long-lived credentials, and access controls evaluated at the moment a request is made. This foundation is far better suited to an environment where an attacker can operate at machine speed and the defender must rely on an identity layer strong enough to contain it.